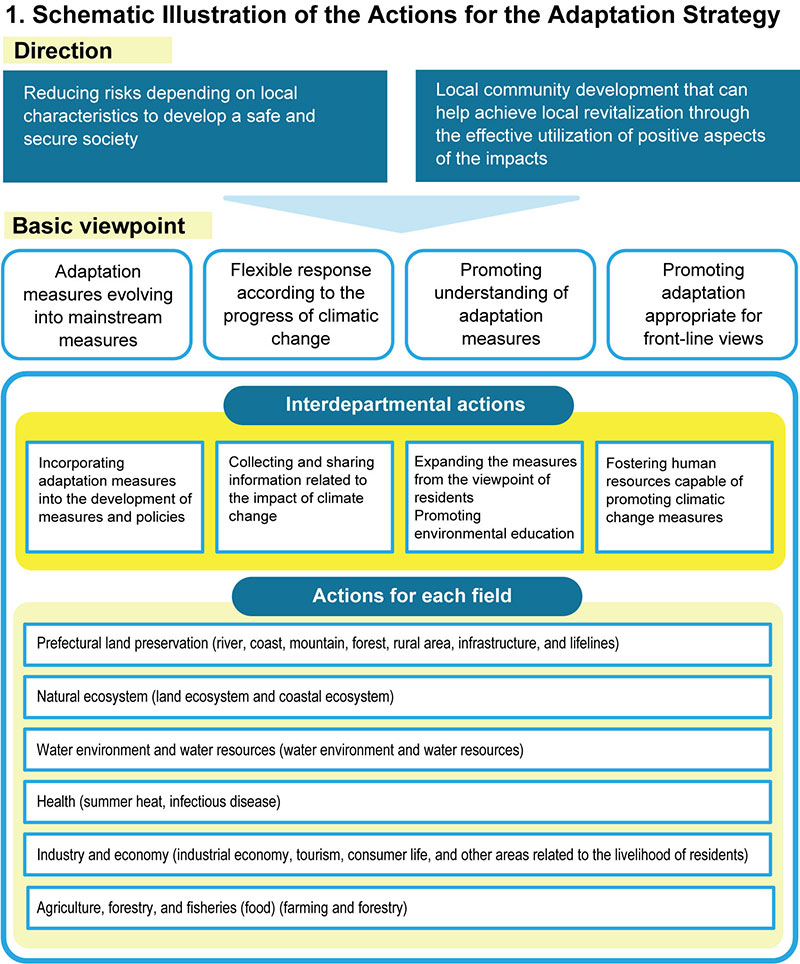

Incorporating mitigation and adaptation into a plan

In January 2017, the Tokushima Prefecture government became the first government entity in Japan to enact a carbon-free ordinance that introduces a full range of adaptation measures. One of the major initiators, Masaji Fujimoto, former manager of the Environmental Capital Section in the prefectural government, developed adaptation measures from scratch, and then formulated mitigation measures, ultimately establishing an incorporative plan in less than two years. The question is how the fast-acting, trailblazing action plan was accomplished. We interviewed the former and current managers of the Environmental Capital Section about the plan.

Creating a One-on-One Relationship Through Interdepartmental Actions

When the Tokushima Prefecture Climatic Change Adaptation Strategy was first developed, I understand the term “adaptation” was much less familiar than it is today. How did you gain momentum for this idea?

Fujimoto (former manager): I was always environmentally conscious, and I had once worked in the Environmental Department. In April 2015, I was assigned to lead the Environmental Capital Section, which led me to ask myself a variety of questions about what I could do in Tokushima. The 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21) was scheduled for that winter. We knew that the Japanese government was working on an adaptation plan. That was when I learned about the two climate change strategies: mitigation and adaptation. I learned that mitigation strategies are almost the same in any governmental organization anywhere in Japan, regardless of whether the measures are about energy saving or recyclable energy. Adaptation measures, however, differ significantly by area depending on local conditions. My new understanding about adaptation strategies made me think, “That’s something we as residents should develop in our own community.” That thought was where the plan started. I began talking with my coworkers, and fortunately, we had input from the prefectural assembly that facilitated our process. Our work then began to progress.

In October 2016, an adaptation strategy was formulated, and the basic policy for adaptation measures was in the Tokushima Prefecture Ordinance for Climate Change Measures for the Realization of a Carbon-Free Society, and was scheduled to be enacted in three months. You were putting your plan into action at extraordinary speed. Did you ever feel that developing the ordinance for the adaptation strategy was a high hurdle to clear?

Tokushima City from the Prefectural Hall with Awaji Island in the background

Fujimoto: Not particularly. This may just be my personality, but I enjoy taking on new challenges. In addition, everyone around me worked hard to make the plan happen.

We often hear from other local government organizations that they are having a difficult time developing their own plan. How did you work with each department?

Fujimoto: We first explained the main gist of the adaptation measures and asked departments to give us their goals and projects in the category of adaptation. Those of us who asked didn’t actually understand what was meant by the term “adaptation.” Despite our being new to the task, each department was already working on projects in line with the concept of adaptation. One example is wakame (brown seaweed), one of our prefectural specialty products. As water temperature increases, the production volume of wakame decreases. Scientists in the prefecture had been working on breed improvement to solve this problem. We presented actual examples of adaptation when we talked with staff in each department, and then decided if their actions could be categorized as adaptation. Sharing the same level of knowledge in our discussions with department staff was important because doing so keeps everyone aware. Meetings and other official forums do not always facilitate candid interaction. If you want to exchange and discuss individual ideas, what comes first is establishing a one-to-one relationship with each department.

When you and the department staff determined what adaptation was, did you have any judgment criteria?

Fujimoto: Honestly, we didn’t overthink judgment criteria. We would consider a measure from a broader perspective. If we felt that a specific measure was more or less related to adaptation, we added that measure to the category of adaptation, that is, as long as both sides felt comfortable. Doing this may have been a bit of a compromise. If, however, our judgment had been too rigid about measures to include and exclude, the work of categorization alone would have been exhausting and time consuming. What matters is not the judgements we made, but how we incorporated adaptation into action.

Omitting Numerical Targets Was Not an Option.

Why divide into six categories, and what is the priority of those categories?

Fujimoto: Because of the current status of Tokushima prefecture, if measures for urban and rural living were combined into a single field, the field would be too small for such measures. That’s why we put the measures into industrial economy and prefectural land preservation. Our basic understanding, however, is that we cover the seven fields of the national government’s adaptation plan. We didn’t prioritize any single category. This is because I thought everything was equally important to prefectural residents. Our prefectural population is aging more rapidly than the national average. With so many societal problems that we, like all other nations, face, my concern is that the immediate challenges, such as the aging of society, will make adaptation to climate change seem like a trivial problem. Climate change is our most significant challenge. We as individuals and as members of our prefecture must do all we can to face up to the challenges of climate change and rethink how we go about the business of our daily life. We in Tokushima also have special geographical and climate characteristics, including steep topography, fragile geological features, and frequent typhoons. We established mechanisms in each of the six categories to reduce those risks.

The adaptation strategy includes indexes and numerical targets. This is a daring attempt, but what made you decide to establish numerical targets?

Fujimoto: I am sure that the national plan had no numerical targets, but numerical targets are indispensable for developing our plans. Progress cannot be measured without numerical targets. The understanding among personnel in the Tokushima Prefecture Government is that if numerical targets are not included in the plan-do-check-act (PDCA) cycle, a plan does not exist. Each project already had its own numerical targets, so we followed that practice, and each department was requested to set targets for new projects.

Is it difficult to reflect the budget in the numbers?

Fujimoto: We look ahead when we establish targets. The ideal is if a budget is already appropriated before we establish a target, but you never know what will happen in two to three years. We try to have a budget that supports our actions, but if there is no budget appropriated for some or part of the actions, we set target values showing what we want to do, that is, if possible. As far as substance goes, there are still parts that we are working on taking action. We believe that when the locals see the residents, they will react positively and begin to address those actions that they themselves can take.

Did you create a special subcommittee to manage the progress of numerical targets?

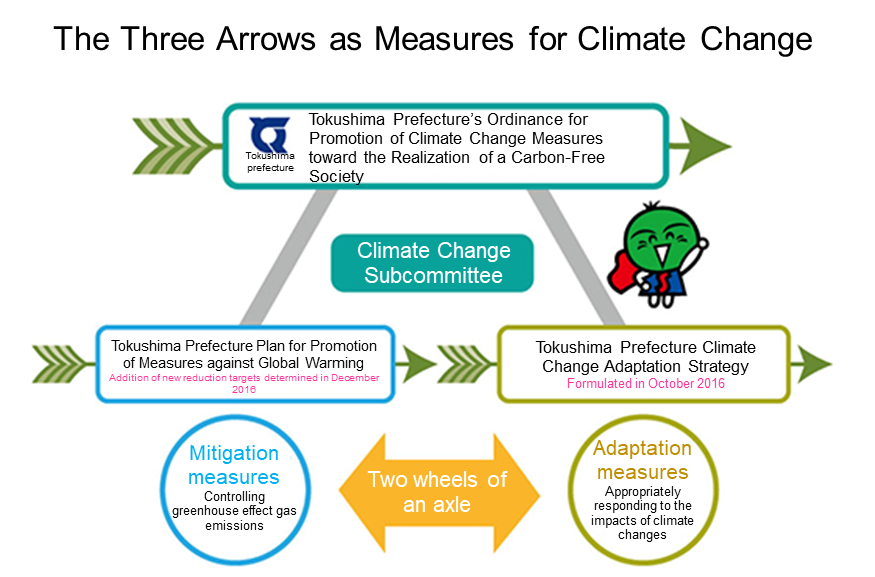

Fujimoto: Yes. We had a section in the prefectural government called the Environmental Action Promotion Department. We invited external experts and created the Climate Change Subcommittee as an environmental council. This subcommittee inspects, evaluates, and manages progress based on the PDCA cycle.

What difficulties did you have developing plans?。

Fujimoto: The Adaptation Plan Support Program of the Ministry of the Environment or the Ministry of Education supports some prefectures, but we are working on developing plans alone. That meant gathering information was difficult. We sought cooperation with the Tokushima Local Meteorological Observatory to get as much weather information as possible, and asked the Observatory to join the Climate Change Subcommittee. For future forecasting by field, we asked each governmental ministry or agency via its respective department in the prefectural government to share forecasts with us. Our most reliable partner was the Japan Meteorological Observatory. I can only imagine how difficult gathering information was for the personnel in charge.

Ms. Tamaoka, how did it feel to actually gather the information?

Akiko Tamaoka (former chief): Each department only had what they were able to gather. We thought hard about where we could get future forecasts for areas other than weather data. We didn’t have A-PLAT at the time, so we got whatever information seemed useful from the S-8 brochures, but the information had many prerequisite conditions. We didn’t know what information would be most productive to incorporate. The national government had already developed a plan, and the reference data was publicly available. We found information in the national plan that seemed related to our prefecture and got an overview. That was very helpful. We didn’t know where to start, so we couldn't systematically accomplish our tasks.

Mariko Aoki (chief): The fields of adaptation sound like a kind of science. I was employed by the prefectural government in an administrative post, and there were many things about the data that took time to understand. I’m now mainly involved in operations related to progress management. I hope there are data and materials that are easier to understand for people with a non-science background.

“A Crisis in the South is an Opportunity for the North”: Effectively Using Positive Aspects of Adaptation

Are prefectural residents feeling a rise in atmospheric or ocean temperatures?

Toshiyuki Kawasaki (manager): Residents are aware of temperature increases in business and in daily life. One example is my cousin who runs a wakame seaweed aqua culture business and says that seeding now comes later than in the past. You won’t get productive results if you seed when water temperatures are high. Fishers of conger eel in Tokushima City, in contrast to my cousin, say their hauls are larger than ever. Conger eel is actually a southern fish that sells at high prices as it is indispensable for summer festivals in Kansai, including the Gion Festival in Kyoto and the Tenjin Festival in Osaka.

Fujimoto: The impacts of climate change are not all negative. Some good aspects, for example, are that you can now catch or harvest things you couldn’t have before, and you can find new tourist spots and even new business opportunities. Last year in our prefecture, we commercialized Akisakari, a new rice variety that is resistant to high temperatures. Akisakari is gaining ground as a new Tokushima brand. The word “adaptation” may call to mind numerous things you feel you need to protect, but that’s not the only image we should have. We need to effectively use those positive aspects that occur with climate change.

Kawasaki: When we think about climate change from the perspective of the entire country, we may have new areas for production. A crisis in the south may be an opportunity for the north. People in the south should seize the opportunity.

Achieving a Carbon-Free Society Through The Three Arrows

Earlier, you mentioned risks unique to each area. What specific examples can you give us?

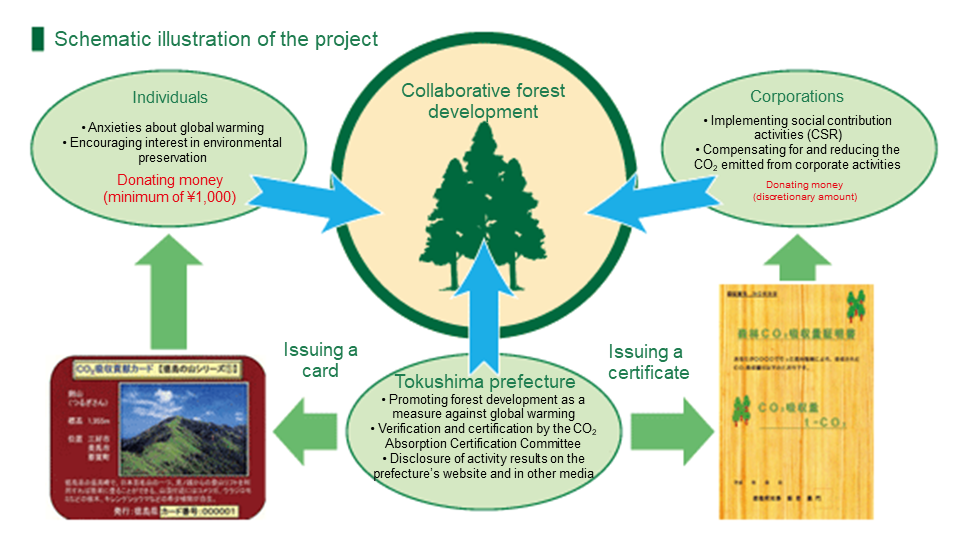

Kawasaki: Forests make up 75% of the land in Tokushima prefecture. When typhoons hit, numerous flood and landslides often occur. This risk increases in hilly and mountainous regions due to depopulation and aging. While vast forests are certainly a risk from the perspective of adaptation, from the perspective of mitigation, forests have a major role in the amount of CO2 absorption. Of course, if forests are unattended to, they won’t be able to increase the amount of absorption.

Fujimoto: Forests have two roles: water retention/adjustment and CO2 absorption. Forest preservation is crucial for both adaptation and mitigation. Because we have a variety of measures to increase the number of forestry workers, more young people have recently taken an interest in forestry, and the number of women in the field has increased. The Tokushima Collaborative Forestry Development Project is a program to develop forests that cannot be maintained through the efforts of landowners alone. Currently more than 100 companies and organizations participate in prefecture-wide forestry development efforts.

Is the prefectural government behind such initiatives?

Fujimoto: Yes, it is. The prefectural government plans to use various local resources unique to Tokushima Prefecture, such as the forest and recyclable energy, to solve local problems through those measures. We implement these measures under “The Three Arrows”. This time the primary topic is adaptation measures, but we kept both adaptation and mitigation as a foundation. We try to create a synergistic effect by implementing each measure and policy from two perspectives: mitigation and adaptation. The compass for this effort is a new ordinance enacted this year: “Ordinance for Climate Change Measures toward the Realization of a Carbon-Free Society”. The phrase “low-carbon” is heard here in Japan, but we observed global trends and decided that “carbon-free” was the more accepted term. We plan to use The “Three Arrows” to reach a carbon-free society before other governmental entities elsewhere do so.

What specific measures do you have to reach a carbon-free society?

Kawasaki: Mr. Fujimoto, our department manager, and a manager from another department achieved something significant, a hydrogen grid concept they developed. Because of their work, a hydrogen station stands at the entrance to the government building. The prefecture currently has six fuel cell vehicles, and about 20 such vehicles are used in the prefecture in total.

Fujimoto: We set the goal of installing hydrogen stations at various areas in the prefecture, including introducing fuel cell buses. We are working on introducing recyclable energy with the aim of achieving a very high target, 37%, while the national government is trying to achieve a target rate of 22 to 24% by 2030.

Fuel-cell vehicles and hydrogen stations

Toshiyuki Kawasaki (left) and Masaji Fujimoto (right)

What do you want to achieve in the future?

Mayumi Kuwamura (vice manager): I was assigned to the Environmental Capital Section last April. The Climate Change Adaptation Plan was mainly developed by Former Section Manager Fujimoto and Assistant Manager Tamaoka. My hope is that Tokushima prefecture can lead Japan and other countries, and that someday I will hear people say that Tokushima has taken the most significant steps to address climate change.

Mariko Aoki: I took over for Assistant Manager Tamaoka, and started working on the ordinance and adaptation last April. Last year I participated in a forum held by the Environmental Capital Section, and was impressed by the vision presented at the forum, especially The Three Arrows. At that time, I had never dreamed I would be involved in this kind of work. Now that I’ve started, I am thinking differently about life and considering how to reduce my own ecological footprint.

Naofumi Takaishi (leader): Our predecessors left us something amazingly wonderful. I am determined to do my utmost to expand and adapt their work so that it becomes mainstream in the future.

Ai Harada (chief): I’m in charge of mitigation measures. We are also aiming high; our goal is a 40% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. To this end, we knew that we must take action and must think of new approaches this year. This does put pressure on us, and there are many other concerns we struggle with, but I’m determined to do my utmost to reach the grand goal of a carbon-free society.

Kawasaki: Mr. Fujimoto is a source of inspiration for me. He’s one of the most brilliant prefectural officials, and he is extremely dedicated. His brilliance and dedication were the driving forces that led to the creation of a new ordinance and adaptation strategy. This was before other local governments in Japan took steps to address climate change. This work will be useless if we do not use action. We have to make our vision a reality. I’m going to do whatever I can to make that reality happen. I’m under pressure, and the work is challenging and crucial. However, implementing these changes and educating residents about what they can do will allow us to do good for prefectural residents.

As the formulators of the new ordinance and adaptation measures, do the two of you have any message you’d like to leave us with?

Tamaoka: Last year, I was totally immersed in the work toward a carbon-free society. I thought that everybody would know the terms “carbon-free” and “adaptation”. Now that I’ve been away from the work, the world around me seems to be asking, “Carbon-free society? What’s that?” I realized that these terms and concepts have yet to reach mainstream society. I’m determined to do everything I can to help my colleagues.

Fujimoto: I’ve been completely immersed in this work for more than two years. We’ve done much, including creating a new ordinance and adaptation measures, but this April, I will be leaving the Environmental Capital Section. Although I wish I could continue here, I’m now going to see the section from the outside. I’m determined to focus on how to make the work grow and expand, and as a private citizen, how to turn words into actions. Environment is a keyword for all of us, no matter where we are or what we do. I will do my utmost as a private citizen to protect our global environment.

(Published on October 30, 2017)