Kanagawa’s heat survey program that involves prefectural residents’ participation is designed to promote interest in climate change.

| Date of interview | June 17, 2022 |

|---|---|

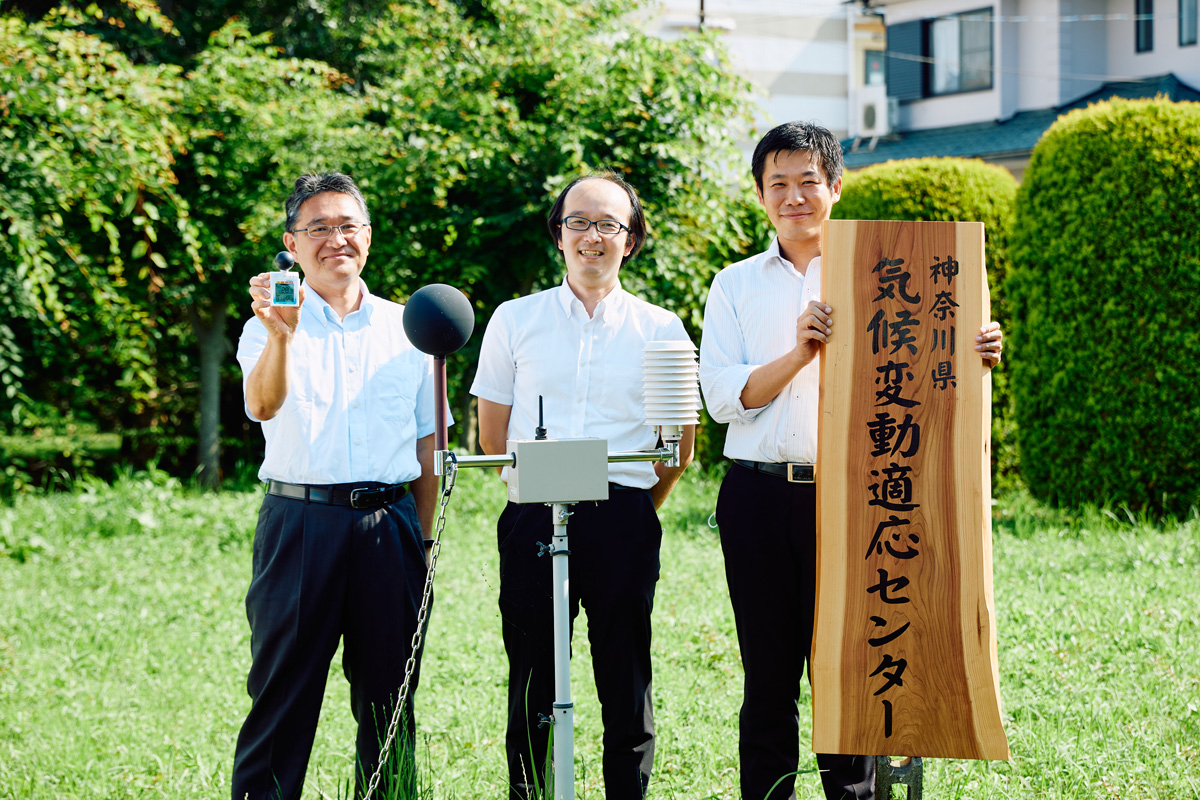

| Interviewees | Environmental Activity Promotion Division Environmental Information Department Kanagawa Environmental Research Center (Kanagawa Climate Change Adaptation Center) Satoshi Tazawa, Senior Technical Staff Member Satoshi Arai, Senior Staff Member Masatake Harada, Senior Staff Member |

Please tell us what led to the creation of the Kanagawa Heat Survey program.

Mr. Tazawa: Kanagawa is a highly populous prefecture with progressing urbanization, due to which the number of hyperthermia cases that required ambulance service has been on the rise in recent years. Therefore, since the Kanagawa Prefectural Climate Change Adaptation Center was established in April 2019, how to address the issue of extreme heat conditions has been one of the key areas of focus for us as they relate to climate change impacts.

One of the challenges with this initiative has been the component of public awareness promotion and education. So the Kanagawa Heat Survey program was created with the notion that, by encouraging the prefectural residents to measure the heat index (wet-bulb globe temperature, abbreviated “WBGT”) data in their local communities themselves, their understanding and consciousness of climate change might improve as a phenomenon that they are closely affected by.

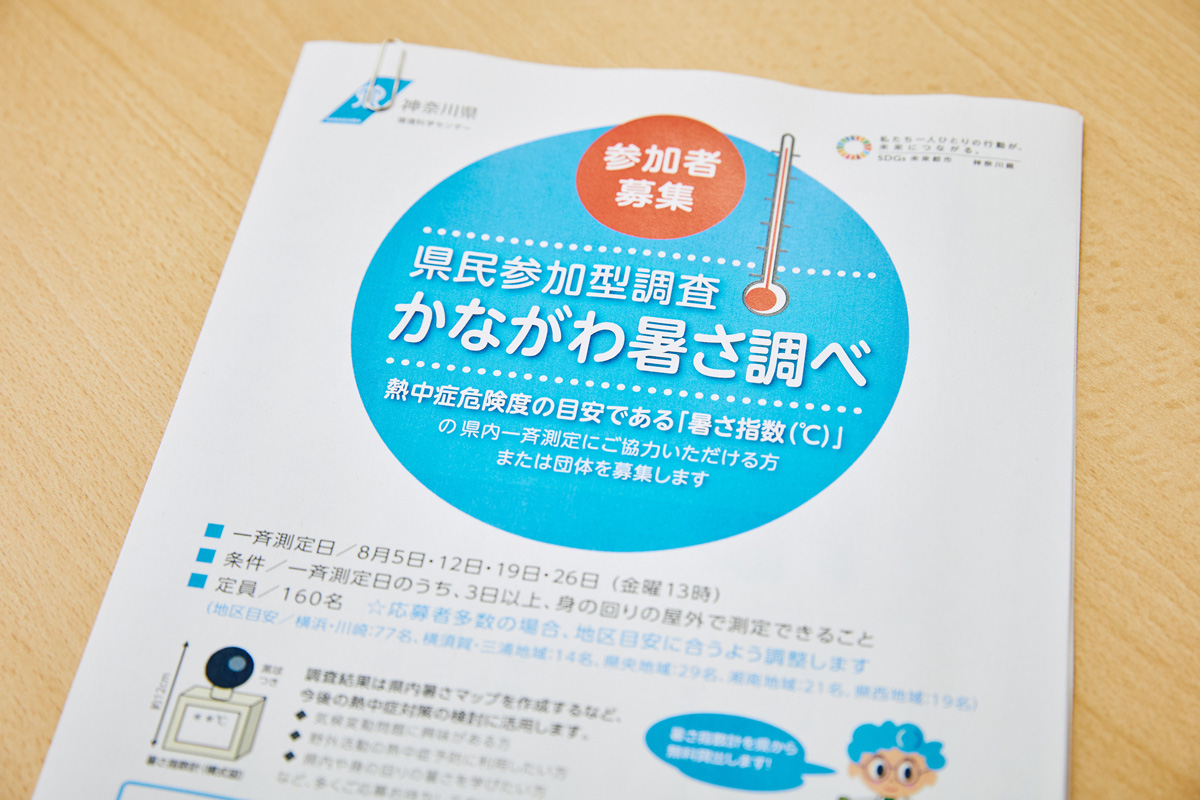

So, we first distributed commercially available WBGT meters across the prefecture and asked the participants to take outdoor measurements in their areas once a week through the entire month of August each year, around 1:00 p.m. on specified dates. In FY2021, we had procured 100 WBGT meters and recruited participants, to which 262 willing residents responded. So for FY2022, we increased the number of available WBGT meters to 200.

In addition, we thought it would be interesting to suggest this program be used for elementary school students’ independent research projects, and assigned a quota reserved for young children’s afterschool clubs. Another point we paid attention to for program optimization was that the participants would be equally spread out across the prefecture, for which we divided the prefecture into several arbitrary blocks and selected participants by drawing lots, etc.

The recruiting period lasts for a month or so each year, during which we publicize the information in the prefectural gazette, social media posts, and newsletters to solicit applications through our electronic application system or by postcard.

So what are the findings in your program so far?

Mr. Tazawa: One particular phenomenon that we thought was interesting occurred in August 2021. The weather was relatively sunny and hot on the 4th and 11th but turned rainy and chilly on the 18th, and the reported WBGT readings clearly reflected the change. As it became sunny again on the 25th and the data reflected it, we were able to verify that the WBGT index also tracked the weather.

Although these measurements were only taken four times during the entire August, the data showed different alert levels between some neighboring towns, etc. We were quite intrigued by this, as it provided a glimpse of what the heat map for the entire prefecture might look like.

How is the progress of your public awareness and education campaign?

Mr. Tazawa: When we ran a questionnaire survey of the participants, one of the questions asked whether they became more active than ever before in implementing measures to prevent hyperthermia after participating in the heat survey program, to which about 30% selected the answer stating they implemented prevention with more care than the previous year. So we interpreted it as an indication that the program had been effective to a degree in terms of alerting people to the risk of hyperthermia.

The questionnaire also included a question that asked whether the participants wanted to take part in the program in the following year, to which over 90% responded positively. In the comment section, we also saw positive responses, some of which said they were glad they got to know what the WBGT index was, while others were apparently astonished to find out how hazardous their outdoor activities were. Such results have given us a confidence boost as to the efficacy of our approach so far.

Meanwhile, we did encounter some surprises, one of which being that as much as 30% of the program participants did not know about the existence of the WBGT heat index. While we had assumed that the general level of interest among the participants might have been high as they found out about the program information we put out and cared enough to apply for it, from this 30% indication, we must infer that the general public’s awareness of the heat index might be lower still.

How has the risk of hyperthermia been trending in Kanagawa Prefecture in recent years?

Mr. Tazawa: In 2018 in particular, the weather was quite hot not only in Kanagawa Prefecture but also across the rest of Japan, resulting in higher numbers of hyperthermia patients that had to be transported to hospitals in ambulances. As the temperature and weather patterns vary from one year to another, it is difficult for us to clearly determine whether those are the effects of climate change manifesting. But it is certain that the number of hyperthermia cases that require ambulance service has remained relatively high since.

We can at least predict that the weather basically would not become cooler than what it is going forward, and with it, the risk of heat-induced illness would continuously rise. Furthermore, as the aging of the country’s population progresses, the number of senior citizens that are more vulnerable to high heat conditions continues to rise also, perpetuating this challenging trend.

So what are the measures you have been implementing to address the situation you have just explained?

Mr. Tazawa: One of the measures is to improve the public’s awareness of the hyperthermia risk empirically by encouraging their participation in the Kanagawa Heat Survey program and to promote their preventive actions based on the WBGT heat index, etc. Another measure we have been taking through joint research with the NIES (National Institute for Environmental Studies) is the in-depth evaluation of the WBGT index data that were previously measured. The goal here is to precisely assess the risk of heat-induced illness through comparative analysis of the collected WBGT data and the number of hyperthermia patients transported to hospitals, including region-specific risk disparities.

As the Ministry of the Environment had only five sites of WBGT measurement in the prefecture for public data disclosure, we always wanted to monitor the status of heat index data distribution more broadly. While the Kanagawa Prefectural Climate Change Adaptation Center does measure additional data itself occasionally, the prefectural residents’ support through the Kanagawa Heat Survey program has tremendously helped us with the expanded monitoring also.

Although the devices used in the program are rather simple and the measurement conditions might not be as uniform as they should be, because our staff are not providing on-site support with the measurement, the data reported by the program participants are still quite useful to us.

WBGT data is also measured on the premises of the Kanagawa Prefectural Climate Change Adaptation Center.

WBGT data is also measured on the premises of the Kanagawa Prefectural Climate Change Adaptation Center.Based on available data so far, do you notice any emerging disparity across different locales?

Mr. Tazawa: As we had expected, the eastern part of the prefecture − where Yokohama City is located − constantly has a high total number of hyperthermia patients requiring ambulance service, due to the municipality’s advanced urbanization. However, our comparative analysis of the same figures but adjusted per population of 100,000 between the urbanized areas in and near Yokohama and the western part of the prefecture revealed that the latter had a higher incidence of hyperthermia. As this finding apparently does not correlate to the corresponding WBGT data in any direct way, it might be attributable to other factors.

As such other factors might possibly include the number of people exercising preventive measures against hyperthermia in each polled locale, as well as people’s different lifestyles and living environments, we are contemplating ways through which to gather such additional information in the future.

Please share with us any specific initiatives you are contemplating for facilitating the prefectural residents’ actions to prevent hyperthermia in the future.

Mr. Arai: Although we have not publicly disclosed the data gathered through the Kanagawa Heat Survey in real time until last year, we are considering disclosing it this year or in the near future. We are hoping that, by our disclosure of the measured heat index data to the public as swiftly as we can, the prefectural residents might perceive the data and the meteorological phenomena behind it as a stark indication of something quite real that would affect them.

Mr. Tazawa: There is also this new project we have embarked upon over the past two years where we produce learning materials relating to climate change for Kanagawa Prefecture. In 2020 and 2021, we created such materials for high school and middle school students, respectively, and we are making them for elementary school students this year.

This particular resource entails a learning cycle where the students first watch a video, then engage in group discussion relating to its content, and internalize the phenomena of climate change manifesting locally. Since the most salient example of climate change to those students might be the hot weather they experience each summer, our materials focus on hyperthermia. So if we can somehow tie that into the Kanagawa Heat Survey program and our other research findings, it could create positive synergistic effects in terms of our public awareness and education initiative.

Are you facing any challenges with the implementation of your learning materials at schools?

Mr. Arai: Since the number of implemented cases is still small, the main challenge we must address at the moment is how to widely promote their use. While we have plans to visit high schools and teach classes there, there is only so much we can do on this front due to the limited number of staff at the Center.

Therefore, as with the learning material production, we are also suggesting to those schools an alternative implementation plan that involves their teachers teaching classes using the materials that have been provided from us. In terms of material content optimization, we are still constantly trying to improve their usability in specific classroom settings, with the support of experts, etc.

Mr. Tazawa: Aside from our suggestion of the material implementation plan to schools, we held seminars for the teachers to advise how our materials could be utilized, which were met with positive feedback from the participants that were mostly considering applying the methods we had shared to teach their classes.

The seminars we offered last year were held online. However, as it was difficult for us and the participants to exchange ideas smoothly, we are hoping that this year’s seminars could be held in person.

Care to share your outlook on the future?

Mr. Tazawa: While the Kanagawa Prefectural Climate Change Adaptation Center has celebrated its five-year anniversary, the outputs from its operation are not quite robust yet. So I want to improve the Center’s public communication activities going forward. As we will strive to provide more relevant information to the public, I hope the prefectural municipalities and private enterprises will be able to take full advantage of it in learning about climate change and formulating their adaptation measures.

Mr. Arai: When people hear the term climate change, they would most likely think of carbon neutrality. So, in order to improve people’s understanding of the topic to introduce the concept of climate change adaptation in addition to mitigation, I would like to initiate an awareness campaign targeting the prefectural government employees first.

Mr. Harada: As the prefectural residents that have participated in the Kanagawa Heat Survey program, etc. are environmentally conscious people to begin with, we must capture the attention of the rest of the prefecture’s population that might not be keen on the topic and arm them with basic information on climate change adaptation in the future. This is not just limited to climate change adaptation, but I would like to keep exploring other ways to widely spread our message so that the public can put it to practice.

Please tell us about the source of motivation for your work. Also, if you have any message for younger generations of people, please share it.

Mr. Tazawa: Because I have always been interested in a whole range of environmental issues since childhood, and now I get to address them as my job, I am feeling a highly positive sense of purpose in what I do. While being a prefectural government employee, I get to handle data for climate prediction. I very much enjoy the process of estimating how the future might turn out and identifying the actions necessary to adequately prepare for it.

When I take my children to a conveyor-sushi restaurant to eat and see the dishes of sushi with inexpensive yet delectable ingredients rotating, I am sometimes overcome by this poignant feeling that when my offspring grow up, they might not be able to eat the same fish in the same manner as we do today. So, in order to reduce the damage being inflicted upon nature as much as possible while my generation is still at the helm, I will continuously dedicate myself to educating the public on climate change.

Mr. Arai: As I was recently reassigned to this post at the Kanagawa Prefectural Climate Change Adaptation Center earlier this year, I frankly thought that what I might be able to achieve as a prefectural government employee could not be much, especially in addressing such colossal topic as climate change. However, as I have come to understand, and compared to mitigative measures, there are so many ways to practice climate change adaptation depending on your environment. In other words, I have eventually come to this realization that it is indeed the solemn responsibility of the governmental bodies like ours to lead the charge against climate change.

As the risks associated with climate change could become increasingly exacerbated and cause significant suffering and anguish to my family and friends as well as to myself, I am committed to doing my job well with a view to creating a society that will avert such crisis in the end while making my children proud in the process.

Mr. Harada: In terms of any message that I might have for younger people, I have always liked this saying “think globally and act locally” since my school days. So I would be delighted if many more people with broad perspectives could join the movement to alter the course of climate change on a global scale, perhaps starting with seemingly mundane tasks like measuring the temperature as a participant in the Kanagawa Heat Survey program.

(Posted on November 16, 2022)