“Hyogo Fishery Environment Observing System” providing real-time environmental information of the Seto Inland Sea

Hyogo Prefecture is one of Japan’s major producers of farmed laver and its production accounts for 20%* of the national market. In the late 1990s, discoloration of laver occurred frequently and the yield seriously declined. The major cause was considered reduction in nutritive salt. The problem has been aggravated by a rise in seawater temperature due to global warming.

Hyogo Prefecture has improved the “Hyogo Fishery Environment Observing System” to grasp the environment of the Seto Inland Sea consisting of Osaka Bay, Harimanada Sea and Kii Channel, all different in nature of water, and utilize for fisheries. The improved system is slated to be put in service in March 2018. We interviewed people at the Fisheries Technology Institute of the Hyogo Prefectural Technology Center for Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries about the improved system.

* Source: 2015 statistics by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries

Real-time water temperature information that indicates the right timing of moving laver to the open sea

How was the decision made to improve the “Hyogo Fishery Environment Observing System”?

Hirofumi Nakanishi: As the “Law concerning Special Measures for Conservation of the Environment of the Seto Inland Sea” was revised in October 2015, Hyogo Prefecture formulated the “Hyogo Prefectural Plan on the Environmental Conservation of the Seto Inland Sea” in October 2016 and started striving for the restoration of “rich sea.” The “Hyogo Fishery Environment Observing System” is one of the efforts.

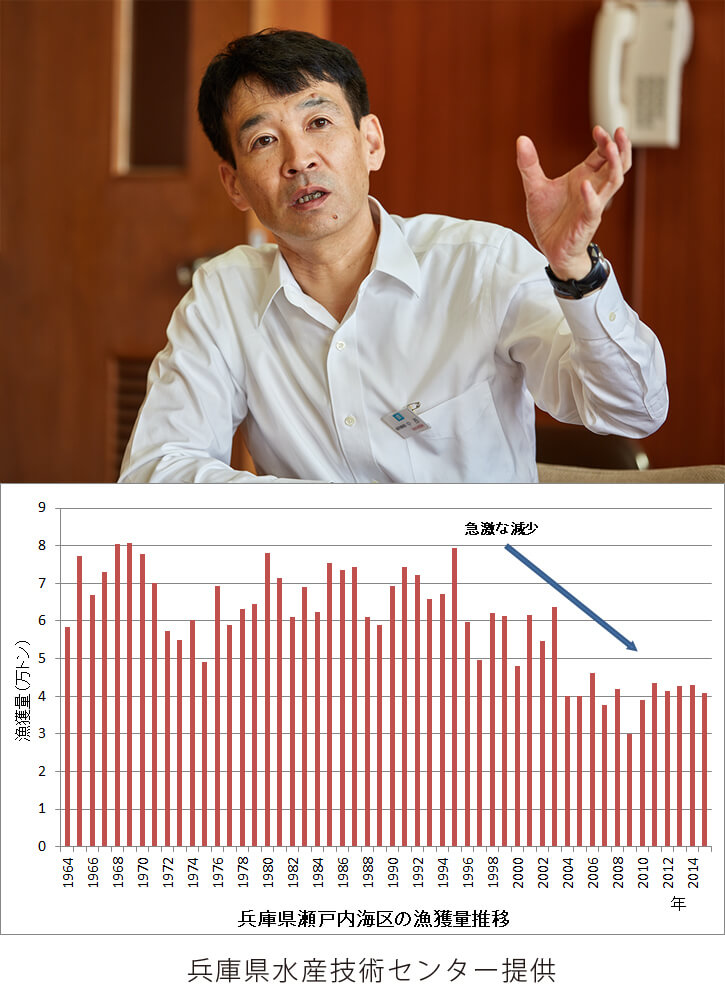

We are particularly focusing on the research to find out the relationship between nutritive salt and fishery resources. We now know that the recent shortage of nutritive salt not only results in the discoloration of laver but also affects other fishery resources. The catch by fishing boat had amounted to more than 60,000 tons till the early 1990s. It plummeted in 1995 and it has been small ever since.

As we are now able to use a budget from a state subsidy (Emergent Project for Fisheries Competitiveness Enhancement and Facility Improvement), we are planning to enhance the system established in 2005 to acquire data for research and help the operations of fisheries operators.

New fishery environment information system

New fishery environment information system

Did you start providing information to fisheries operators in 2005 when the system was established?

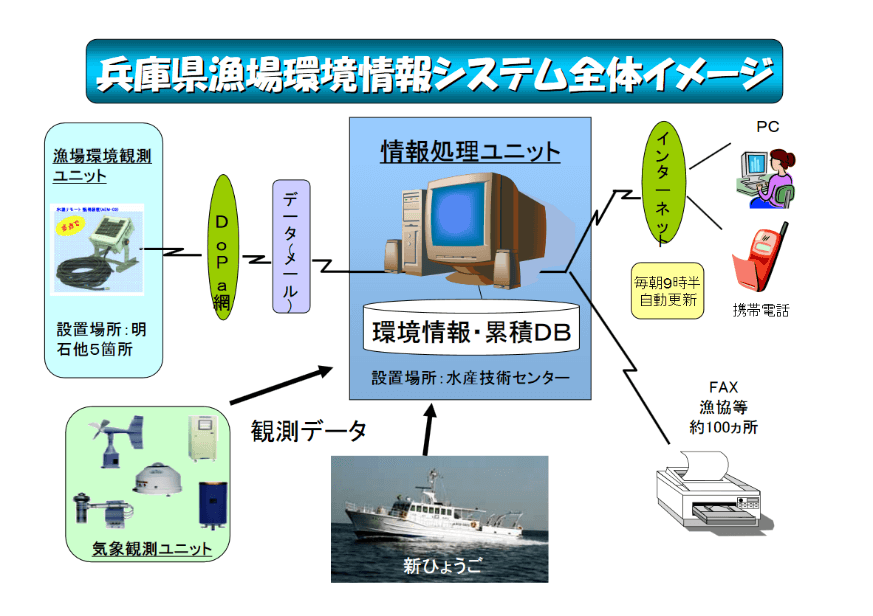

Nakanishi: No. Since 1973, we have conducted hydrographic observation and nutritive salt measurement in Harimanada Sea, Osaka Bay and Kii Channel using a survey ship the center owns and provided information. We were providing information once a week. Later, as fisheries operators said they wanted to have the information more frequently, we have decided to provide it in real time. That has led to the current “Water temperature observational information.”

How are the fisheries operators use the “Water temperature observational information”?

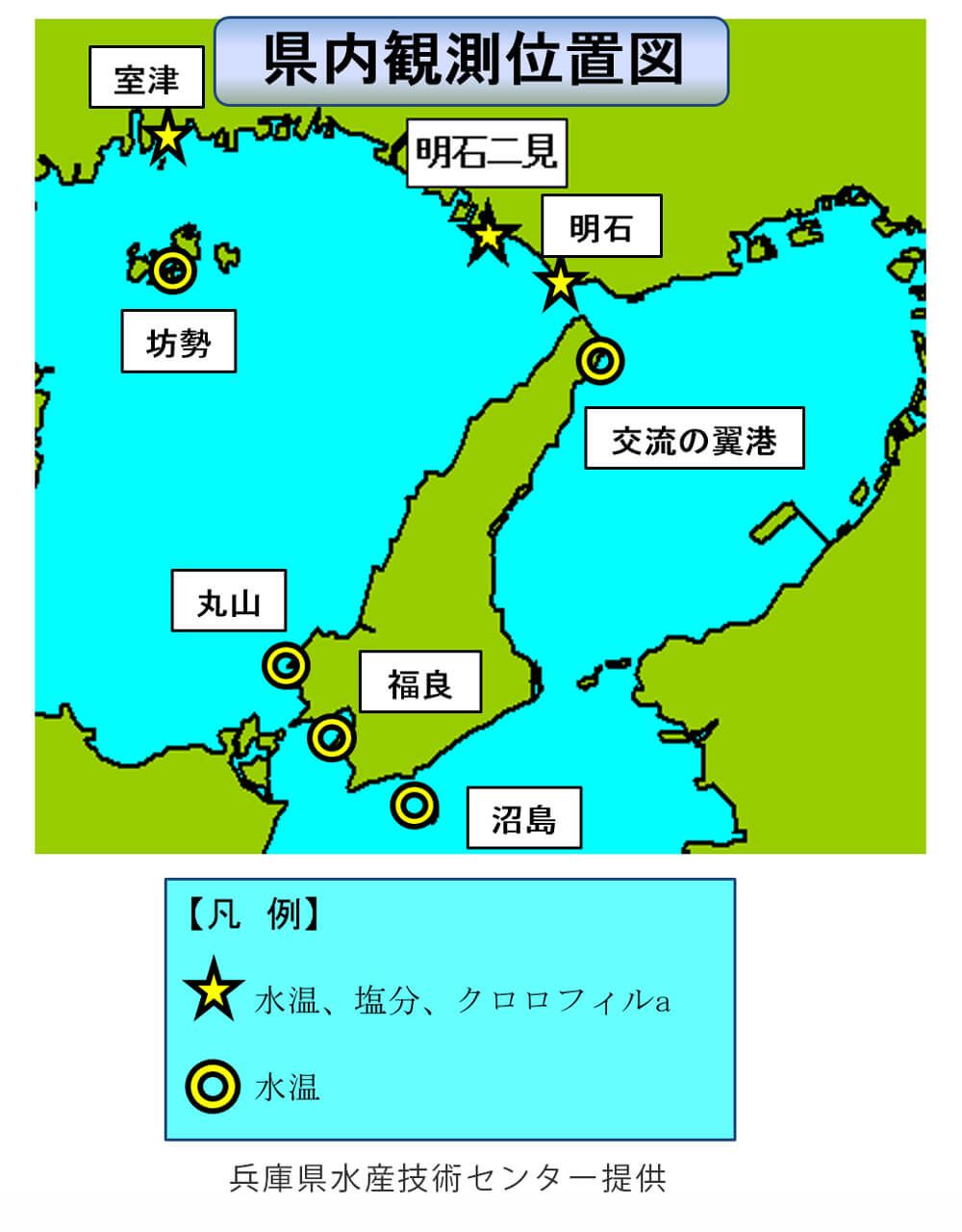

Kenya Oishi: Laver is farmed in most of the coast of the Seto Inland Sea. The “cooperative sales of laver” was 15.8 billion yen between December 2015 and May 2016. Laver is an important marine product and it accounts for about 35% of all the fisheries production in the prefecture. This system was originally intended to provide information for laver farming and started as observing stations installed around Akashi. Naturally, it is mainly used by laver farmers.

Kyosuke Niwa: Laver farming requires a “seedling raising”* period to grow seedlings in the open sea. To determine when to start this period, water temperature is critical. The farmers check water temperatures every day and start seedling raising when the temperature reaches between 23°C and 23.5°C. When starting “net stretching”**, the farmers also need to check the water temperature as water temperature must be at an appropriate level.

Oishi: Water temperature data are shown in four categories, current temperature, previous day’s average, average on the same day of the year before and the normal value during the past 10 years separately for different depths. They provide at-a-glance comparison between a trend of this year and the normal value. The data also includes a graph of changes in daily average water temperature for the past month.

*Seedling raising: Planting seeds on nets and growing seedlings to a certain size

**Net stretching: After seedling raising, stretching nets on the sea surface

Increasing the number of observation points from 6 to 8 to provide more information users require

The “Water temperature observational information” include salt and chlorophyll levels besides water temperatures. Particularly, chlorophyll is not a familiar word. What do we learn from those two data?

Niwa: Chlorophyll is a green substance in plants. Chlorophyll in the sea corresponds to the total amount of phytoplankton. Phytoplankton is feed for zooplankton and small fish. If a chlorophyll level is high in an area, the area makes a rich fishery. Oysters also feed on chlorophyll and thus its level indicates whether there are a lot of nutrients for them. It is useful for Nishiharima, where there are many oyster farms.

On the other hand, if the chlorophyll level is high in a laver farm, risk of discoloration is heightened. Phytoplankton feeds on nitrogen and phosphorus in the sea. If a type of phytoplankton that survives with low nutritive salt proliferates, it eats up nutritive salt necessary for the growth of laver. Farmers use the data together with our center’s periodical observation result of nutritive salt level for their farming management. For instance, they harvest earlier if the nutritive salt level falls.

Nakanishi: Near Akashi Strait, where the tidal current makes complicated movement, salt and chlorophyll data are used to grasp the state of ocean current and movement of water. The salt level in the water coming into Osaka Bay is different from that going out from Harimanada Sea. We can roughly tell how migratory fish is moving using those figures.

That means the information is also handy for fishermen using fishing boats besides aquaculture farmers. Are most users fisheries operators?

Kazutaka Miyahara: To tell the truth, quite a few anglers seem to be using the information. Many fisheries operators use the information but they are not watching it all the time. For example, farmers use it as a reference for their discussions in the community at certain stages of farming. The information is very often used as a material for forming consensus. That is because the same information is sent to fisheries cooperatives periodically by fax or email.

Oishi: The other day, we shut down the system for several hours for maintenance and we soon received a phone call saying “I cannot see water temperature data.” We were surprised that there were people always checking the system. That person was a fisheries operator. We also receive inquiries from the lay public. The users of the “Red tide information” include people outside the prefecture transporting living fish. For example, it is used to determine the route for transporting living Hamachi, Japanese amberjack, from Kagawa Prefecture to Kobe.

Please talk about main improvements to be made this time.

Nakanishi: The number of observation points is six at the moment. We will add two points, one in Nishiharima having many oyster farms and the other in Seidan with many wakame seaweed (Undaria pinnatifida) farms to cover the whole Seto Inland Sea area.

We are going to provide the survey ship with automated nutritive salt observing equipment and our center with a database for unified management. With unified management, we will provide information to fisheries operators proactively.

Oishi: The improved system will be more user-friendly. At present, data are automatically transmitted to the center at 8:30 in the morning via cellphone radio waves, automatically aggregated at 9:00 and posted. After improvement, data will be updated every three hours. The system is originally intended for PC users but it will be also accessible to smartphone users. For instance, a user can check the data while working on a ship at sea.

The sea surface temperature of the Seto Inland Sea has risen by 1°C in 40 years.

You have been observing fishery environments since 1973. How have seawater temperatures changed in the data collected for the past 40 years?

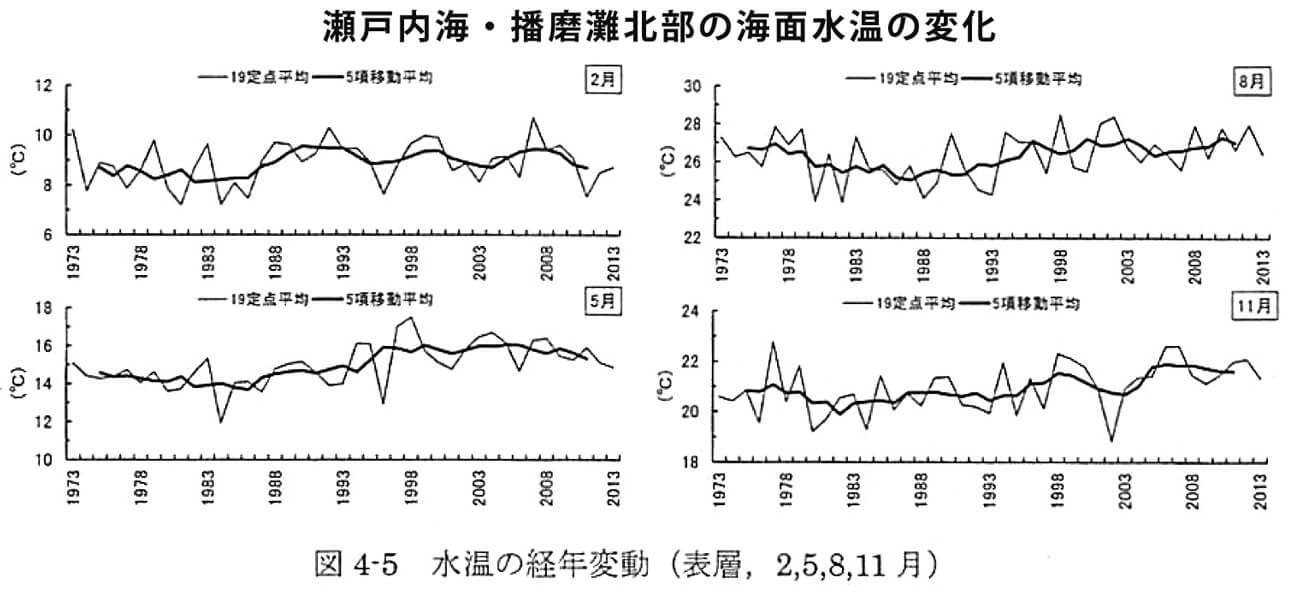

Miyahara: In this sea area, significant temperature changes are observed during the autumn and winter months. In the 1980s, the seawater temperatures were low. In the 1990s, the temperatures began to rise. The average sea surface temperature has risen by 1℃. Changes in seawater temperature are often compared to difference in latitudes. Some experts say that the current temperature is equivalent to that in an area 500 km south from here.

* “Five-member moving average” of a year is an average of annual average water temperatures of five years including that year.

Source: Result of 40-year shallow sea stationary observation of the Seto Inland Sea bloc (long-term changes in sea state)

That is a big change. How has the rise in seawater temperature affected the fisheries industry of Hyogo Prefecture?

Miyahara: As water temperature declines slowly in autumn and winter, time for moving laver and wakame seaweed for rearing in the sea tends to be delayed and the farming period is often shortened. In fact, laver is moved to the open sea 10 days to two weeks later than before.

In oyster farming, a fall in water temperature in autumn is a key factor that determines the quality. When the water temperature declines, oyster begins to accumulate nutrients in the body. If the timing is not right, the oyster won’t be meaty.

In the Sea of Japan, Sawara, Japanese Spanish mackerel, now comes from the East China Sea. In the past, Sawara was not caught in the Sea of Japan but the catches of Sawara increased abruptly from the 1990s. Now, it is caught even in Hokkaido. The factors are considered to be an increase in the number in the East China Sea and a rise in the temperature of Japan’s coastal waters.

On the Seto Inland Sea side, Sawara is essential for autumn festivals and sells for a high price. On the Sea of Japan side, it is still inexpensive. Therefore, it is transported and sold in Okayama or other areas on the Seto Inland Sea side or even abroad.

Nakanishi: Catches of wild fish cannot be controlled. It will be important to consider proactive utilization of resources newly made available by the impacts of global warming. As to Sawara caught in the Sea of Japan, our prefecture has not taken action. It is a great challenge to be addressed.

(Posted on February 22, 2018)

Related Sites (Update:Octorber 14 2022)