Choosing adaptation-related measures from the action plans of individual departments and putting them together into a cross-departmental plan by trial and error for four years

Nagasaki Prefecture, located in northwestern Kyushu, has a mild climate and boasts the largest number of islands in the country. Nagasaki abounds in fishery resources with the second largest fish catch among prefectures. As regional efforts for climate change adaptation were urgently required, Nagasaki Prefecture was among the first to bring a perspective of adaptation to the action plan, “Nagasaki Prefecture Action Plan for Global Warming Countermeasures,” formulated in April 2013. To lay out specific efforts for the action, Nagasaki released “About Nagasaki Prefecture’s Global Warming (Climate Change) Adaptation Measures” in November 2017. We interviewed Masahiro Yamaguchi, Manager of the Environment Policy Section and Tetsushi Fuji, Assistant Manager. They are engaged in the promotion of cross-departmental measures based on 102 adaptation measures selected from the medium- to long-term plans of individual departments.

Indicators for impacts not assessed. Days of trial and error.

Four years after the Nagasaki Prefecture Action Plan for Global Warming Countermeasures was formulated in FY 2013, how did you finally complete the adaptation plan setting out specific efforts for the action?

Yamaguchi: In the Kyushu area, the Kyushu Regional Environment Office had been running the “study commission on global warming impacts and adaptation measures in Kyushu and Okinawa regions” (hereinafter referred to as the study commission) to drive climate change adaptation since 2009. In February 2014, a report meeting on Kumamoto Prefecture as a model was held in Nagasaki Prefecture. Taking advantage of the opportunity, we started formulating an adaptation plan. I had just been transferred to the department. I and two other members, feeling our way, read books and other literature on climate change to find out how we should analyze climate change impacts in Nagasaki and promote adaptation. While studying, we found a clue on how to promote an adaptation plan in the 2014 report of the Environment Research and Technology Development Fund (S-8). Based on it, we decided to conduct simulations of impact assessment ourselves and considered buying map information software. But, we found that it was very difficult to use the software. We concluded that it was difficult for the Environment Department to conduct an impact assessment alone. We outsourced the “global warming impact analysis and adaptation measure development for Nagasaki Prefecture” to private businesses. It took four years to complete the plan.

You had a hard time collecting information on climate change impact assessments and adaptation measures. What exactly were the problems?

Yamaguchi: As the indicators for impact assessment in S-8, which we used as a reference, were designed for the whole country, it was difficult to develop local indicators. S-8 covered only five items; agriculture, water resources, flood disaster, forest ecosystem and health. There wasn’t enough information for climate change impact assessments and adaptation measures on our prefecture’s important industries, marine fisheries and migratory fish. The governor was also concerned about adaptation measures for fishing industry and the Environment Department conducted surveys. However, there were few references and most of them were in English. We consulted the Faculty of Fisheries of Nagasaki University and National Fisheries Research Institute but we could not obtain information necessary for an analysis of climate change impacts on migratory fish. It is still a problem how we should integrate adaptation measures in fisheries into the plan.

When you examined adaptation measures in fisheries, what did you find difficult specifically? What findings do you think will be helpful?

Yamaguchi: Nagasaki Prefecture is surrounded by the sea and benefits directly from that. We have difficulty about the field of fisheries, in particular. Extensive research data like ocean data are available from the Japan Meteorological Agency but it is extremely difficult to examine and analyze the data from a perspective of climate change. Taking farming for example, if the appropriate temperature range for every fish species is known, finding a farm according to changes in seawater temperature will be an adaptation measure. Such data will be very helpful. If there is an expert, we will visit for advice. The Fisheries Department may have various findings. However, the Environment Department needs to grasp climate change impacts on fisheries extensively and the same is true of other fields.

Choosing adaptation measures linked with the plan of each department

Although no indicators were available, you paid attention to Nagasaki’s important industry, fisheries, and made strenuous efforts. The adaptation plan contains as many as 102 adaptation measures. How did you choose them?

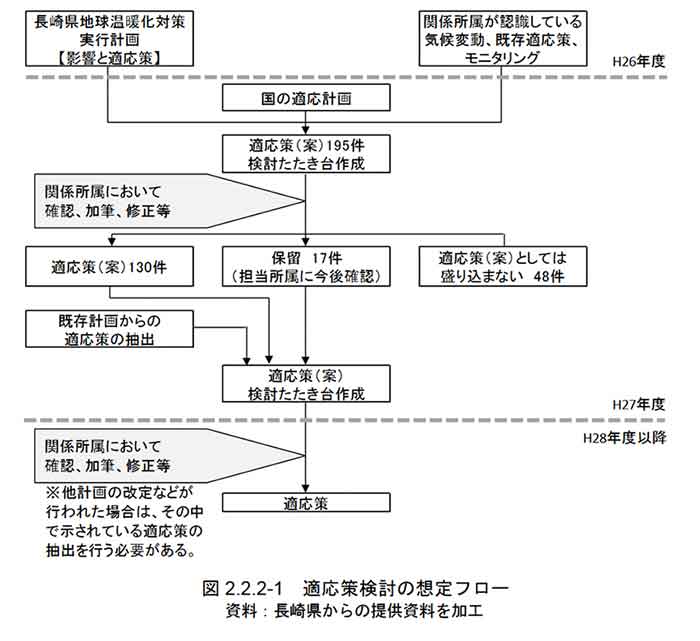

Yamaguchi: In September 2014, we had a review meeting of relevant prefectural departments. First, to deepen their understanding of adaptation measures, we organized a lecture by an expert. To choose adaptation measures, we asked each department to think of their relevant impacts and adaptation measures based on the climate change impacts and adaptation measures included in the action plan for global warming countermeasures and submit all those they could come up with. The Environment Department organized the submitted impacts and measures to make it easy to discuss and fed them back to each department. Final decision was made by the staff of each department. We compiled the results into the “FY 2014 report on the global warming impact analysis and adaptation measure development for Nagasaki Prefecture.” In November 2015, the national adaptation plan was formulated. We asked all the relevant departments for collation with the plan by mailing list. We reviewed the items in each field in the plan to see whether there was any item we could employ while also utilizing the findings from the “FY 2015 support project for climate change impact assessment and adaptation planning by local governments” (hereinafter referred to as the model project) by the Ministry of the Environment. We could choose 195 adaptation measures. We examined those 195 measures with a consultancy engaged in the model project to find those suitable for Nagasaki Prefecture. We employed 130 measures, put 17 on hold and didn’t employ 48. After each department checked whether the chosen measures were included in the existing plan (reference 2), we finally decided on 102 adaptation measures (Figure 1). That is why those adaptation measures are linked with medium- and long-term plans of individual departments.

The numerous adaptation measures were chosen through the collation with medium- and long-term plans based on the policies of relevant departments. In that process, did the Environment Department check the action plans of all the departments?

Yamaguchi: To see which plans of the departments chosen adaptation measures were linked with, we checked the medium- and long-term plans. Why it is important the measures are linked with medium- and long-term plans of the departments is because the progress management of adaptation measures needs to be linked with the plans. All the departments have their regular operations and it is difficult for them to do progress management separately for adaptation only. It is ideal that the progress management of each medium- or long-term plan is closely linked with that of adaptation measures. In 2020, the action plan for global warming countermeasures is to be reviewed. How to incorporate the adaptation measures in the plan is another challenge. The Environment Department has an organization called “21 Nagasaki Environment Creation Promotion Section” to control the progress of other plans. Utilizing this organization, we are considering reviewing the plan every year. Most plans of departments, including our action plan, are reviewed every five years. If the awareness of the importance of adaptation measures spreads in the prefectural government, the possibility may be raised that adaptation measures are incorporated into the plans on the occasion of review. We hope that the Environment Department can establish such a system.

Nagasaki prefectural office

Importance of information sharing – Climates may vary from region to region but there are common issues for adaptation.

How do you communicate information to private businesses and residents besides the relevant prefectural departments?

Yamaguchi: In September 2014, we had a review meeting in the prefectural government. In March 2015, the Environment Department organized a seminar on climate change adaptation for prefectural departments, municipalities and private businesses. Adaptation measures are not a problem of the government only. We must widely disseminate them.

To that end, we ask the climate change action officers for cooperation. The officers are working to foster the awareness of global warming prevention measures among citizens. Nagasaki Center for Climate Change Actions has included the topic on adaptation measures in their training course since FY 2016. That helps deepen the officers’ understanding and information on adaptation is conveyed from the officers to residents. We do not have any particular activity to approach private businesses. We have talked about the issue at a seminar organized by the prefecture in March 2015 and the symposium “Science of climate change and our future -- Dialogue between IPCC and Nagasaki citizens” held by the Ministry of the Environment in January 2015. We will continue to seize opportunities to increase the awareness widely.

Climates vary from region to region even within Japan. What do you think of the significance of sharing information among different local governments?

Fuji: If each prefecture has to formulate a plan alone, there is a limit. As the activities by the Kyushu Regional Environment Office using a model project shows, it is natural that local governments cooperate in tackling this issue. Even if climates vary, the necessity of a perspective of “adaptation” is common to all the local governments. There are problems specific to particular region but there are also problems they can share.

Yamaguchi: We started examinations in FY 2013 and outsourced the global warming impact assessments and adaptation measure development in FY 2014. In FYs 2015 and 2016, we utilized the model project of the Ministry of the Environment. It took four years of twists and turns to finally establish the adaptation plan. Half of the period was spent on impact assessments. We had to make special efforts as there were no indicators for impact assessments nor information about adaptation measures in the field of fisheries. If we make the most of the experience and cooperate with other local governments in impact assessments and adaptation measure development covering several prefectures, the period of four years can be reduced to two years. In that sense, it is significant to exchange information with other prefectures. The study commission by the Kyushu Regional Environment Office was also very effective.

The Climate Change Adaptation Act enacted in June suggests support by Local Climate Change Adaptation Centers. Are there any roles you require of the center?

Fuji: It is ideal that prefectural departments know all the latest findings but that is not the case. It will be becoming more and more important to establish a system for constantly sharing information with Nagasaki University, consultancies well-versed in climate change adaptation and any other entity having the latest findings.

Yamaguchi: It will be difficult for all the cities, towns and villages to make their adaptation plans. Someone must play a role in “traffic control,” for example, having the prefecture share information it has with cities, towns and villages and referring them to relevant departments. I think the center should provide experts and coordinators who understand climate change impacts in various fields, such as agriculture, forestry, civil engineering, health service and welfare, besides fisheries we struggled with and providing information necessary for developing adaptation measures to those impacts.

In conclusion, please tell me what you find rewarding in working on climate change adaptation as a member of the Environment Department.

Fuji: Adaptation measures are not to be implemented by the Environment Department. Each department is the key player. Our job is to support them to ensure that they can develop policies with a perspective of climate change impact added based on the latest information. The Environment Policy Section work behind the scenes. That motivates me. Also, working on climate change adaptation has brought home to me that the adaptation is an issue near at hand.

Yamaguchi: Adaptation is not a new independent field but tasks of organizing the existing policies of relevant departments from a perspective of adaptation in a cross-departmental manner. The issue may not be familiar to many people but it is closely related to our everyday life and industry as in the example of a disaster due to torrential rain. We are trying to disseminate that widely. When we successfully convey the idea, if only slightly, I will be feeling my job rewarding.

(Posted on November 2, 2018)

Related sites

- Study commission on global warming impacts and adaptation measures in Kyushu and Okinawa regions

- Report of FY 2015 support project for adaptation by Nagasaki Prefecture

- Report of FY 2015 support project for climate change impact assessment and adaptation planning by local goverments

- Reference 2: Report of FY 2015 support project for adaptation by Nagasaki Prefecture -- References

- Science of climate change and our future -- Dialogue between IPCC and Nagasaki citizens